Artists in Conversation: Hardish Virk x Hassan Hussain

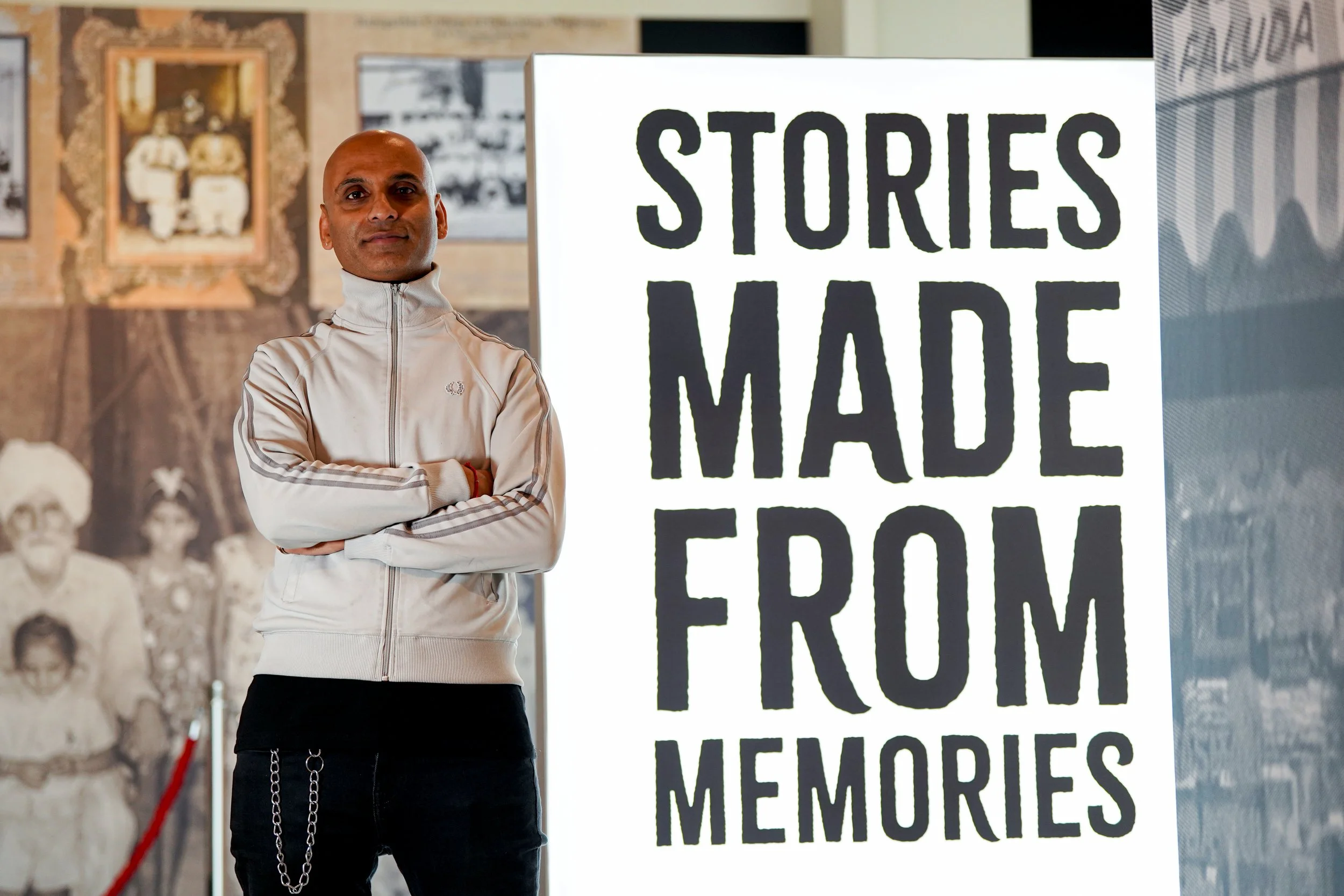

‘Stories That Made Us - Roots, Resilience, Representation’ is a dynamic new immersive exhibition currently on at the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry.

Hardish Virk began his career as an actor, director, producer, writer, visual artist and DJ in the late 1980s. By the 1990s he was learning that, in order to affect positive change in the arts and cultural sectors, he needed to be more strategically involved. This has led to over thirty years of working with cultural organisations and artists in the UK and Europe, advising on staff recruitment and training, artist and audience development and diversifying stories and programming. Community and stories have always been at the heart of his work and were the inspiration for the living museum of South Asian stories idea he first announced in 1996. Hardish has developed his archiving and curatorial experience and skills over the years, which led him to set up the South Asian heritage project, ‘Stories That Made Us’ in partnership with Coventry Artspace in 2021. ‘Stories That Made Us - Roots, Resilience, Representation’ was conceived and co-curated by Hardish Virk.

Dr. Hassan Hussain is a lecturer, writer and cultural facilitator. Having completed a PhD investigating the de/construction of gay men in contemporary British theatre, his practice explores the transformative effects of queer histories and lived experiences on present and future iterations of identities, communities, and (sub)cultures. Hassan is particularly invested in situating his work within the city and has secured ACE funding to redress the underrepresentation of queer South Asian voices in British playwriting. Moreover, his involvement in coordinating and producing a diverse array of research panels, festivals, and live-art events – primarily within Birmingham – further enriches his practice. He is also a board member for Fierce Festival and a member of Culture Central’s Inclusive Network.

Hassan Hussain: Personal archives are at the heart of the exhibition and people spoke a lot about the emotional weight of bringing family stories into a public space. So, with this in mind, how did you navigate the balance between the private and the public when curating this work? And what responsibilities did you feel in making those intimate histories visible?

Hardish Virk: I've been working on ‘Stories That Made Us’ as a project for nearly five years. That gave me time to process the personal stories, address my relationship with these stories through objects like photographs and audio recordings. In the early days when I would listen to my mother's recordings, they'd remind me of listening to her on the radio in the 1990s and when I would look through photographs, that would trigger all sorts of memories. But going over the process of archiving, cataloguing, curating two exhibitions, I have managed to respond to working with personal objects and stories in a more removed and professional mind-set.

I had a three-fold role. One was an artist, the second was an archivist and the third one was a curator. So even though I've removed myself emotionally from the objects and the narratives within the exhibition, which are specific to my family story, there was still a weight of responsibility. That responsibility was very much about ensuring that the stories are told with integrity. I am telling the stories of my father Harbhajan Singh Virk and my mother Jasvir Kang without any consultation or involvement from them, as they are not alive anymore.

The way in which I approached that, was by letting the archive drive the narrative as the stories were in the artefacts and objects. So, if we look at the living room, it is very much my father's story in the 1970s and that was based on my father’s archive, the Virk Collection at Coventry Archives. I used my mother's radio broadcasts and her short stories and poetry in Punjabi to drive that narrative in the radio station. In both cases, it felt right to celebrate them as artists and activists.

Now, the bedroom's a whole different story because that's my story. It was about growing up as a teenager in 1980s Britain. So that was about what I was watching, what I was listening to, my friendships, where I was going to socialise, my interests in theatre and film. I also wanted to tackle some of the more serious issues. And one of the things that I tackled was the racist attack that took place on me in 1986. But I was keen it wasn't a victim narrative. So, my response was that it was about resilience and defiance.

I'm also aware once the exhibition is in the public domain, I don't own that story anymore. I have to, you know, stand away from it and let the public engage with it.

Hassan Hussain: Yeah, that's really beautiful - something that really stuck out to me in what you said is the kind of process[es] of establishing yourself in the three-pronged roles as you described: the artist, archivist and curator.

Hardish Virk: That's right.

Hassan Hussain: It’s a very interesting way of looking at your parents, and your family as bodies or pieces of art - which links nicely to the next question in terms of process.

A lot of the visitors to the exhibition described it as a living breathing archive with a lot of discussions about it being sensory, familiar and emotionally resonant. In regard to that, can you talk about your creative processes a bit more and in shaping an environment that feels both deeply personal and accessible?

Hardish Virk: Yes, so I come from a storytelling background - I used to work in theatre. I wanted to tell a central story, and I wanted that central story to be personal and to be human. The family story was chosen as a central story that runs at the heart of this exhibition.

I wanted to frame that within an educational narrative. To me, it was really important, not least because of my own experiences of growing up in Britain. Our nuanced stories are very rarely told within education, within arts and culture, within the media. I'm talking about the contribution we've made to every facet of British life you know, in terms of, health, education, art, culture, media, politics, you know, across the board. Often, we're told segments of our story within a school environment, which is a starting point for a lot of young people to learn about any history, let alone their own history. So, it was really important for me to present that in a way in which it was accessible and how I saw that was through a pictorial timeline of our stories which frames the whole exhibition from the start right to the end. I was keen to ensure that this story went back to the 1600’s with the East India Company going over to India and colonising the country through its business interests. So that's a starting point and as you work your way through the timeline, there are some key milestones and key things that are happening in India but also its relationship with Britain and how that develops over the centuries and we work our way up to 2010. So that's over 400 years of history.

My ambition is to have a building-based living museum of South Asian stories in Coventry. The idea was to have a blueprint for this living museum in an exhibition space, and this exhibition is that blueprint with the different room settings.

These ideas were shared with Dominic Bubb from the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, who has worked on major exhibitions before, whereas I'm coming in with experience of small-scale exhibitions. He not only has experience of putting on large scale exhibitions but also understanding gallery spaces, measurements, techniques, etc. Then we recruited Shaniece Martin as the Archives Assistant. She continued the research into South Asian history, which I had started. We commissioned my sister Manjinder Virk from Riverbird Films to make the two films and my sister Pavenpreet Kaur to direct the audio recordings in the radio station. They're connected to the family story but also work at a high level in film and theatre making.

We also worked with people from the Herbert like Jack Nelson bringing on board technical expertise. We worked with a company called Blind Mice Design, specifically Selina Goodfellow who worked with me and Dominic in creating the massive graphics you find throughout the exhibition, the timelines, the photographs, the text, the newspaper headlines, the legislations, that big wallpaper that's in the bedroom. So, it was a collaborative process. I'm involved in everything. I signed off on everything. We also had builders and technicians who had the blueprint for the exhibition, so they just went ahead and built the walls, installed what they had to and work through the audio and visuals to make the exhibition come alive. But they did come back to me and ask, "Hardish, is that okay? Is that working for you?”. I went through the curatorial process of ensuring that the cases were designed the way I wanted them and the space looked the way I wanted it to be.

Hassan Hussain: And all that stuff looked 10/10, I remember the timeline was like this big, inspirational piece that a lot of people mentioned feeling very connected to after viewing the exhibition. I think seeing a South Asian historical timeline on this wall in an institution like the Herbert brings such a visceral feeling - especially for the South Asian community - and this led to a lot of discussion centred around the relationship between communities and cultural institutions.

So, could you talk a bit more about what this collaboration with the Herbert specifically has taught you about working with institutions, and what do you hope institutions might learn from projects like yours?

Hardish Virk: It's been interesting because I have worked with institutions throughout my professional life in different contexts and roles. But this was really interesting because what I learned was that this is an institution. So by that very nature, institutions work institutionally, they work in a particular way. I had to push back on some things to ensure that the integrity and authenticity of the exhibition came through. Be it in the way in which I wanted things to be presented and who was involved. There was no resistance from them, there was a lot of learning. That pictorial timeline is interesting because if you go to a lot of galleries and museums across the country, you'll find timelines which are text based. I've never seen a pictorial one. In the exhibition, the timeline has the South Asian timeline, then you have my family timeline, and then you have a more generic timeline at the top. I said the visibility of South Asian communities is fundamental to the visibility of the stories we're telling in the exhibition. If you only have text on the South Asian timeline, then you are continuing that narrative of keeping us invisible. I wanted to ensure that we have images of South Asian pioneers on the timeline. I'll give you an example - it was important that I have people like Shaheed Udham Singh and Shaheed Bhagat Singh - two key freedom fighters visible on the timeline. So, if you know who they are, you'll get the context of the whole exhibition by seeing their faces. Very rarely would you find their faces in any historical context in institutions across this country. Also, for those that didn't know who they were, were on an educational journey. Learning takes place within an organisation through the process of working with somebody like myself but also from the stories we're telling and how we tell these stories. They're learning about our histories, they're thinking about the other collections that they own and how they collaboratively tell stories in community centred exhibitions in the future. I learned a lot as well.

Hassan Hussain: Thinking about the future is a nice segway into the final question. Many visitors have said that the exhibition has inspired them to explore their own archives or family histories. So, with this in mind, what do you hope the longer-term legacy of the project will be for you, for the community, and for the inclusive network of people working in the cultural sector in the West Midlands?

Hardish Virk: The ambition is to have a living museum of South Asian stories in a house. We needed a blueprint, something tangible, physical to present to potential stakeholders. I'm now thinking it's not a house. I'm thinking now it's a warehouse - a big open ground floor space because we can just recreate a living museum in an exhibition space, but on a larger scale, it makes it more accessible for wheelchair users, for example.

The other thing is about the relationship between the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum with existing collections held in the Coventry archives. So this process I believe has tightened the relationship between Coventry Archives and the Herbert Art Gallery, not least because they've been loaning objects from the Virk Collection for the exhibition.

The Herbert’s looking at how visitors from the gallery space are encouraged to visit the archives, so people can learn more about Coventry Archives but also learn about the value of archives. What is the relationship between an institutional archive and personal archives? That brings in a bigger conversation I'm having with the sector. For example, the value and language of personal archives versus the value and language of institutionalised archives. How do we interpret personal archives within institutional spaces or public exhibitions? How do we add value to the storytelling behind objects exhibited in public institutions? There has to be a story. Who tells that story? Who do you work with to ensure that these stories are told with integrity and authenticity?

I'm encouraging people who come to see this exhibition to tell their own stories in the reflection space that's built into the exhibition, to respond to the exhibition, to use this as a catalyst to record their own stories of their grandparents or you know, learn more about their ancestry and then tell their children.

So there's different elements of legacy to this piece of work. And then there's the public - to inspire them to value their own personal stories and look at ways in which they can capture and document their stories and maybe tell their own stories in spaces like the Herbert, like I have.

Hassan Hussain: Yeah, that's beautiful. Honestly, I could chat to you all day. Thank you for your time and for engaging so wonderfully with the questions.

Hardish Virk: No worries, thank you for your time and thought that went into these questions - thank you for working on this.

Hassan Hussain: My pleasure.